Download the .pdf version here.

Introduction

“Public participation means to involve those who are affected by a decision in the decision-making process,” reads the IAP2 definition. “It promotes sustainable decisions by providing participants with the information they need to be involved in a meaningful way, and it communicates to participants how their input affects the decision.” Involving many different stakeholders with varying expertise and experiences ensures that a diversity of opinions is considered throughout the decision-making process, which results in a stronger conclusion with greater support. It is also the cause of conflict in these processes.

Conflict management in relation to public participation is a key area of interest for IAP2 Canada members. In 2014 IAP2 Canada published the Research Initiative Report, which presented findings of a 2013 survey aimed at understanding the research and learning priorities of the membership. 93% of respondents indicated an interest in learning about research-based trends, best practices, and innovations in public participation through an accessible format. Conflict management surfaced as a priority research topic through this survey.

This white paper aims to meet the needs of IAP2 Canada members by providing insight into current research in the area of conflict management in public participation. It offers practitioners an overview of a number of new and exciting approaches, and demonstrates how they can be applied to the daily work of IAP2 Canada members to support continued growth and improvement in the industry and more effective public participation.

Causes of Conflict in Public Participation

Conflict “is present when two or more parties perceive that their interests are incompatible, express hostile attitudes, or […] pursue their interests through actions that damage the other parties,” says Schmid (1998, cited in Engel 2005).

Conflict management “is the practice of identifying and handling conflicts in a sensible, fair and efficient manner that prevents them from escalating out of control” (Engel and Korf, 2005). Good conflict management recognizes the value of “constructive conflict” in encouraging participants to engage and communicate to develop a shared understanding of the issue at hand (Van de Vliert et al. 1999). Conflict can benefit public participation by offering a deeper level of discussion and deliberation, leading to stronger solutions that are more reflective of the community (Leung et. al 2004; De Dreu 2006).

Conflict in public participation results from discrepancies in values, interests, and levels of power (Rahim 2001). These factors can be determined or affected by different experiences, backgrounds, opportunities, identities, and abilities. Cultural differences in addressing conflict, variation in conflict communication styles, and how different communities understand and respond to conflict in public meetings are growing challenges (Cai and Fink 2002; Bernstein and Norwood 2008).

These disparities are further heightened by individual “conflict management frames,” which Gray (2003) describes as the strategies participants use to respond to conflict. Conflict management frames are developed through the participant’s knowledge and past experiences in situations of conflict. It is the way participants interpret and “frame” a dispute, which in turn determines the approach to resolution. Framing a conflict as insolvable is unproductive and restrictive, whereas framing a conflict as a challenge can encourage joint problem solving.

Leung et. al (2005) propose that there are two main forms of conflict: task and team. Task conflict results from “differences in judgement” and a lack of consensus on the project objectives and decisions (Amason 1996). Team conflict is based on emotional, interpersonal struggles (Jehn and Mannix 2001). Practitioners need to be able to identify the form of conflict, and then select an appropriate strategy for mitigating that conflict. The goal of conflict management in public participation is to reach an outcome that all parties can support. Consensus is not often a realistic expectation in a conflict environment, but mutual understanding can be achieved with the right tools and strategies and can lead to a sustainable decision. Public participation practitioners must be equipped to address conflict and ensure inclusive and productive processes.

Conflict Management Methods in Public Participation

All four conflict management methods profiled in this section have two important operating assumptions in common: that all participants must be equal, and that conflicts (and in turn, resolutions) are based in values. Treating all participants with the same respect and giving the same weight to their contributions helps to create an environment of understanding and empathy, which can mitigate conflict. Identifying shared values within a group is necessary to find solutions that align with those values, and helps to frame conflict as an opportunity to collaborate in achieving shared objectives.

The Circles method fosters an environment of mutual respect to ensure all participants have opportunities to participate and their contributions are weighted equally, including the facilitator’s, which reduces discrepancies in power and thus manages conflict. Deliberative Participation is similar to Circles in that it revolves around group conversation, however instead of sharing stories and opinions, Deliberative Participation groups actively work towards finding a shared solution through discussion and debate. Gamification manages conflict by engaging participants in artificial games and tasks that require group problem solving, which helps participants to collaborate in reaching a shared goal. Dramatic Problem Solving similarly relies on artificial premises, but through role-play it requires participants to interact with each other and actively confront their conflicts.

The four conflict management methods profiled in this paper are only a few of the strategies that are being developed, improved, and assessed. There are a number of other methods that may be of use to IAP2 Canada members, but in the interest of providing a concise resource have not been profiled in this paper. Interactive Reflection, a term coined by The Consortium on Negotiation and Conflict Resolution (CNCR), has been used for years to resolve group conflicts. The strategy relies on participants to willingly deliver and receive constructive criticism and capitalize on the newfound awareness of their own behaviour to communicate openly and work through conflicts collaboratively. PPGIS (Public Participation and a Graphic Information System) has been used to encourage community engagement in planning and resource management, but there now exist opportunities to extend the tool to support conflict resolution. A prototype of a PPGIS conflict-resolution model was recently tested in a study of Lantau Island, Hong Kong, and showed promising results (Zhang & Fung 2013).

Method 1: Circles

Circles are derived from traditional practices of Indigenous Peoples of North America and have a long history in conflict management. This approach to problem solving is focussed on strengthening communities, fostering mutual understanding, and building relationships. Circles operate within the Indigenous concept that everyone is related to the problems around them, and the belief that participants can address conflict by “nurturing shared values” (Ball et. al 2010).

Circles gather a group in a physical circle facing one another to engage in structured dialogue. The facilitator, or “Keeper,” opens the Circle with a ceremony that is reflective of the topic at hand to focus the group and develop shared guidelines for interaction. These shared guidelines create a self-governing process for the Circle. A “talking piece” is passed around the group. This is a small object and only the participant holding the talking piece can speak, which allows everyone an opportunity to participate and encourages active listening. Participants are invited to share personal stories that relate to the discussion. During the Circle, the Keeper is an equal participant and is not expected to remain objective. The role of the Keeper is to ensure the Circle follows the guidelines. The Circle process includes four stages: Getting Acquainted, Building Relationships, Addressing Issues, and Developing Action Plans.

“You would never get that level of detail and understanding in other formats,” says Dr. Wayne Caldwell, co-author of Doing Democracy with Circles and Interim Dean of the Ontario Agricultural College at the University of Guelph. Caldwell began using Circles 10 years ago to address conflict over water quality improvement strategies between farmers and cottagers along the Lake Huron shoreline. “It gives everyone a voice, and brings everyone to the same level.” Caldwell stresses that the key to successful Circles is getting participants buy into the shared values and guidelines early in the process.

Circles excel at managing conflict because they focus on generating mutual understanding and “create spaces for healing and transformation” (Ball et. al 2010, 3). The goal of Circles (which is always made clear to participants) is to find an outcome that is sustainable in that all participants feel is acceptable, even if it is not their first choice. Circles engage participants on mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual levels through respectful communication and storytelling to uncover the shared values. This approach minimizes the perceived differences or conflicts amongst the group, and highlights similarities and common goals.

Relationship to IAP2 Public Participation Spectrum

“Management has to be prepared to give up power,” says Caldwell. Circles are best employed in the “Collaborate” and “Empower” stages of the Spectrum, as one of the key elements of Circles is that all participants are valued equally as decision-makers.

Using this Method

There are four stages of preparing to use Circles. Facilitators must first determine whether or not a Circle is suitable for the process by asking if the parties (clients and stakeholders) are willing, if they are motivated to find a solution, and if there is sufficient time to ensure a thorough process. Caldwell suggests asking “how will you make it feel that it’s something people will be accepting of?” He cautions that some may perceive the process to not be serious enough, but that it can have tremendous value if the participants are cooperative.

Once the Circle’s suitability is determined, the facilitator must prepare for the Circle by identifying which stakeholders need to participate for the process to be valid. This includes asking who will be impacted, and who has the knowledge or skills needed to discuss the topic. If the issue is already contentious and key stakeholders are polarized, preparation for the large Circle may involve holding smaller, separate Circles with various interest groups to develop an understanding of their concerns, needs, and desires and help to develop trust in the process, which can mitigate conflict early on.

Examples of Use

“I use elements of Circles in almost everything I do,” says Caldwell, who stresses that the method can be applied in a wide range of environments from public participation to office management. Circles are regularly used in communities, schools, families, workplaces, and the criminal justice system because they have the ability to accommodate multiple scales. Circles need to be maintained at a manageable size so all participants can engage, but Caldwell suggests that they can also be used in large-scale public participation processes by selecting representatives from various interest groups. These key stakeholders can participate in the main Circle, and others can observe the process. “Ontario’s Greenbelt creation process in 2005 involved over 1,000 people attending town hall meetings,” says Caldwell. “It could have been interesting to have a smaller Circle in the middle of the room with different people representing different interests, and then viewers of the Circle process around that as observers.”

Method 2: Deliberative Participation

Deliberative Participation also relies heavily on identifying shared values. This method engages a diverse group of participants in thoughtful conversations on the challenges at hand and the strengths and weaknesses of possible solutions to lead to a decision based in the shared values of the group (Gastil 2005). Similar to Circles, Deliberative Participation gathers small groups together to debate and discuss an issue (Woolley 2010). It ensures that all participants have opportunities to contribute to the conversation, actively listen to other participants, and create a respectful environment (Gastil 2008).

Deliberative Participation is effective in managing conflict because it creates an environment where all participants are equal and have equal opportunities to participate, share their opinions and values, present reasoned arguments, develop an understanding of the opinions of other participants, and come to rational agreements together (Woolley 2010; Barton 2002). This method proposes that traditional large group format processes, such as town hall meetings, rely mainly on one-way communication that is “more likely to promote adversarialism” (Nabatchi 2012, 704). The small groups of Deliberative Participation processes minimize conflict by encouraging teamwork and the identification of shared values.

Relationship to IAP2 Public Participation Spectrum

Nabatchi’s diagram below shows a modified IAP2 Public Participation Spectrum with corresponding communication modes. Deliberative participation can take place from “Involve” to “Empower” on the Spectrum, although it is most valuable when used in an environment where all participants have opportunities to not only share their opinions, but also to play equal roles in discussions under the assumption that a mutually agreed upon decision or plan will be reached.

Using this Method

Deliberative Participation is most effective when participants bring different perspectives and experiences, and when participants are prepared and knowledgeable about the subject at hand. This can be accomplished in environments when possible participants are identified through a public selection process that is open to people in a selected geographical or political community, rather than a stakeholder selection process. Selected participants can then be provided with materials beforehand to help foster deeper and more informed discussions. A small table format with groups of 8-12 participants and a facilitator is ideal for use of Deliberative Participation. Tables can deliberate and then report back to the room. Multiple sessions are ideal for managing conflict to allow for time to identify, address, and move beyond challenges to result in a shared decision (Nabatchi 2012).

Examples of Use

Deliberative Participation is reflected through a number of commonly used public participation structures, including 21st Century Town Meeting, National Issues Forums, Deliberative Polling, and the Citizens Jury (Nabatchi 2012).

Method 3: Gamification

Games, or elements of games, are increasingly used to mitigate conflict and encourage greater participation in public processes. This is a broad category and can include digital games, card games, board games, sports, street games, etc, all of which are united by their inclusion of artificial conflict, rules, and measurable outcomes. Games are an increasingly popular tool in facilitating public participation and in managing conflict within those processes.

Game theory has long been used to model interactions and predict the outcomes of conflicts. The most famous example is the “prisoner’s dilemma.” Developed in the 1940s, game theory is a mathematical method to calculate gains and losses, based on the assumption that “players” (participants) will make rational decisions in conflict situations (Rapoport 1974). Lerner (2014) disputes this, arguing that participants will also address conflict with irrational decisions. Lerner proposes that engaging participants in playing games is a more effective strategy for managing conflict: “Games make conflict safer by making it more artificial.”

Games can address various conflicts, including individual vs. individual, individual vs. group, individual vs. system, group vs. group, and group vs. system. Team building games, capacity-building games, and analysis and decision-making games all encourage “collaborative competition,” which motivates participants to work together to achieve shared goals and objectives and links participation to outcomes (Lerner 2014).

“By accepting and structuring conflict, programs can make participation more enticing, productive, and fun” (Lerner 2014). The competitiveness inherent in games encourages participation by a wider range of players to solve the conflict presented, and rewards collaboration amongst participants.

Relationship to IAP2 Public Participation Spectrum

Games can be used in every aspect of the IAP2 Spectrum, from “Inform” to Empower.” This method is flexible because games are often specifically developed by the facilitator for the project at hand, and can thus be tailored to the goals and objectives of that project. One game may seek to simply share information with the public in a fun and interesting way, while another may seek to address identified conflicts and engage participants in working together to solve them.

Using this Method

Games designed for public participation must share certain characteristics. They must involve some sort of challenge to be solved collaboratively, which can reflect the real-life conflicts within the process. Games must also have clear rules and a defined outcome that is understood by all participants, and that will be rewarding. As with all public participation processes, games must be designed to accommodate varying scales and contexts. For example, some games may not be appropriate for groups involving participants who speak different languages and will have difficulty communicating (Lerner 2014).

Examples of Use

Games are often used in participatory budgeting processes, including in Lerner’s 2009 Toronto Community Housing initiative to identify and evaluate possible community improvement projects. Games can also be used effectively to engage children in community visioning and development projects.

Method 4: Dramatic Problem Solving

Dramatic Problem Solving, or DPS, is similar to games in that it is an interactive facilitation method that engages participants in role-play (Hawkins 2012). DPS relies heavily on cyclical action research, which involves participants as researchers and decision makers revisiting and reframing discussions and challenges. It also draws on Schwarz’s facilitated problems solving structure and Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed (which is also referenced in game development for conflict resolution).

Theatre techniques, such as “Forum Theatre” can be used to help a group analyze issues and resolve conflicts. Forum Theatre (Schroeter, 2009) engages both actors and audiences, thereby accommodating large groups. After presenting a short performance reflecting the group’s topic or problem, the actors begin again and invite audience members to interrupt the performance and direct the actors with the hope of changing the outcome. This creative format encourages collaboration amongst all participants to achieve a shared goal, and allows participants to work through conflicts using verbal and nonverbal communication in a safe environment that is partially separated from reality (Hawkins and Georgakopolous 2010). The intense interactivity of DPS invites participants to confront conflicts on both emotional and logical levels, and motivates participants to solve them in order to reach a shared performance goal.

Dramatic Problem Solving process chart with cyclical action resarch (Hawkins and Georgakopolous 2010).

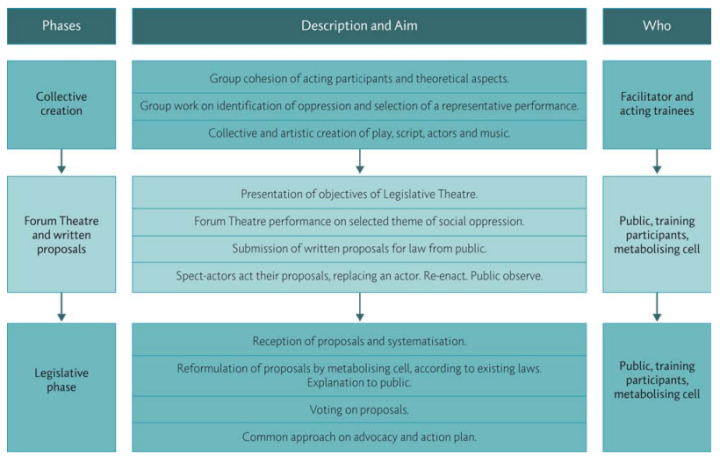

“Legislative Theatre” is another branch of social theatre that was created by Boal and is employed as the next step in DPS after Forum Theatre. The goal of Forum Theatre is to raise consciousness, and the goal of Legislative Theatre is to develop and confirm policies. “Legislative Theatre, as an artistic methodology for active citizenship, creates a process of collective reflection to produce solutions to community conflicts” (Salvador 2012).

Relationship to IAP2 Public Participation Spectrum

Different forms of DPS align with different areas of the Spectrum. As noted above, Forum Theatre raises consciousness and therefore aligns with the “Inform” and “Consult” areas of the Spectrum. Legislative Theatre is more appropriate for “Involving, “Collaborating,” and “Empowering” as it involves participants in decision-making.

Using this Method

DPS is an extremely interactive process and requires willingness and commitment from all participants. DPS can be used in different contexts and in various scales. In a small group setting, all involved in the process can participate as actors. In a larger context, roles can exist for actors and audience members who are invited to interact at key points in the production. Led by a facilitator, the process begins with a group discussion to establish a shared vision of the conflict and its possible resolutions. Participants are fully involved in the creation of the dramatic piece, its performance, and its reiterations.

Examples of Use

DPS was used at a large scale by the Costa Rican Humanitarian Foundation (CRHF) to engage a group of single mothers in the La Carpio neighbourhood of San Jose, Costa Rica, to address local challenges, including the cleanliness of streets and other public spaces (Hawkins and Georgakopolous 2010). This process was so successful that it was used again by the CHRF to address public health issues in the region.

Methods Comparison |

||||||

| Method | Summary | Scale | Examples | Benefits | Challenges | More Information |

| 1: Circles |

Group discussion and storytelling in circles.

Everyone is equal.

Everyone takes turns speaking, including facilitator, who does not remain neutral.

Focus on relationship and community building. |

Best for smaller groups, 8-15. Larger groups can participate by electing representatives of various interests.

|

Used with schools, families, work places, and communities.

Criminal justice system to create alternatives to incarceration for youth and to improve the lives of prisoners |

Bridges differences between cultures, ages, genders, geographies, status etc.

Engages participants on an emotional level – |

When key parties are polarized, it may be necessary to hold individual Circles with each party before the main Circle.

The time a Circle will take is very difficult to estimate, and it is recommended not to stop the conversation before it has naturally completed.

|

Doing Democracy with Circles, 2010, by Jennifer Ball, Wayne Caldwell, and Kay Pranis. |

| 2: Deliberative Participation |

A diverse group engages in conversation to deliberate a problem.

Conflict is reduced by treating all participants as equal players.

Decision making based on facts and values.

Requires that participants be well informed of the issues at hand. |

Best for small groups of 8-12. |

Determining whether or not wind energy generation farms are publicly acceptable in seascapes (Woolley 2010). |

Allows for thoughtful, detailed discussion of a topic.

Helps participants to better understand each other’s views and experiences, fostering empathy and reducing conflict. |

Concern that it could exclude stakeholders if only people in powerful positions are invited to join the deliberation.

No guarantee that outcomes will align with the goals of the governing body or client.

Integration of small group discussions and proposals within larger framework. Integration requires scaling up small table discussions to share with all stakeholders.

|

Democracy in Motion: Evaluating the Practice and Impact of Deliberative Civic Engagement, 2012, edited by Tina Nabatchi, John Gastil, Matt Leighninger, and G. Michale Weiksner. |

| Methods Comparison | ||||||

| Method | Summary | Scale | Examples | Benefits | Challenges | More Information |

| 3: Gamification |

Engages participants in playing games and collaborating to achieve a common goal and resolve a conflict.

|

Different games are appropriate for all scales. |

Toronto Community Housing (TCH) participatory budgeting 2001-2012 (Lerner 2014).

Mind Mixer (online participation tool).

|

Creating a strong link between participation and outcomes/rewards encourages greater participation.

|

Creating or tailoring games that reflect the issues at hand and address conflict. |

Making Democracy Fun: How Game Design Can Empower Citizens and Transform Politics, 2014, by Josh Lerner. |

| 4: Dramatic Problem Solving |

Interactive theatre based facilitation.

Creates a safe space to work through conflict using role play. |

Can be used at various scales as active roles exist for actors and audience members. |

Community in the La Carpio neighbourhood of San Jose, Costa Rica, addressing group-identified issues (Hawkins and Georgakopolous 2010)

|

Creates a safe space outside of reality to acknowledge and work through conflict in a collaborative way. |

Requires substantial participation from stakeholders.

Requires substantial time. |

Dramatic Problem Solving: Drama-Based Group Exercises for Conflict Transformation, 2012, by Steven Hawkins. |

Conclusion

As is apparent through the conflict management methods reviewed here, value disparity is at the root of the most challenging disputes. Values influence perception of issues, challenges, and possible solutions (Woolley 2010). Within all conflict management methods, it is vital for practitioners to identify and understand participant values, distribute power evenly, acknowledge interests, and find common values to successfully resolve conflict (Nabatchi 2012; Leung et. al 2013).

This insight into current research in conflict management and public participation will hopefully expand the toolkits of IAP2 Canada practitioners, and allow for more collaborative processes that result in supported decisions and move communities forward.